Today’s Globe & Mail ran a little piece on The Long Summer of the Carny.

The carnival workers of Conklin Supershows don’t see the big-city glam of the CNE or the PNE. From April to October, they travel small towns, setting up shopping mall midways and county fairs. It’s a fading way of life with few rewards.

A few weeks ago, they had set up a sad little show in the nearly empty parking lot of the East York Towne Centre, with rides for the kiddies, a couple of bored elephants shuffling back and forth under an awning in the July heat, and some small performing dogs racing back and forth in an enclosure.

I was reminded of Sara Gruen’s wonderful book, Water for Elephants, which is a must-read for anyone who is fascinated by the circus, elephants, or the Depression-era hobo life.

As a young man, Jacob Jankowski was tossed by fate onto a rickety train that was home to the Benzini Brothers Most Spectacular Show on Earth. It was the early part of the great Depression, and for Jacob, now ninety, the circus world he remembers was both his salvation and a living hell. A veterinary student just shy of a degree, he was put in charge of caring for the circus menagerie.

It was there that he met Marlena, the beautiful equestrian star married to August, the charismatic but twisted animal trainer. And he met Rosie, an untrainable elephant who was the great gray hope for this third-rate traveling show. The bond that grew among this unlikely trio was one of love and trust, and, ultimately, it was their only hope for survival.

After Jacob puts Silver Star down, August talks with him about the reality of the circus. “The whole thing’s illusion, Jacob,” he says, “and there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s what people want from us. It’s what they expect”

Dave Weich of Powell’s Books interviewed the author. An excerpt of the interview:

DW: Is it true that you’d never been to a circus before starting your research for Water for Elephants?

Sara Gruen: It’s true. I had no history whatsoever. No interest, no connection to anyone associated with the circus. I grew up in northern Ontario. I don’t know if they didn’t come up that far or if I just never went, but if I did go it made such a little impression on me that I didn’t remember it.

DW: What wound up being your favorite act?

SG: In the end, the liberty horses… A person, usually a beautiful woman, comes out with a group of twelve horses typically, sometimes all white, sometimes black and white. She stands and makes signals with whips in the air, and she talks to them, and they obey her.

I have a horse, and I think it’s very cool that they can get horses doing that with no restraint and no halter.

DW: Marlena is that woman in Water for Elephants.

SG: Yes, and in fact I modeled her act after ones I had watched.

DW: And Rosie was based on a real elephant?

SG: Several elephants, yes. There was actually an elephant that would pull her stake out of the ground to go and steal lemonade, and then she’d go back and put her stake back in the ground and look innocent while they blamed the roustabouts.

DW: One of my favorite details in the book, having nothing to do with the circus, describes the boys in the hobo jungle: when they sleep, they take off their shoes but tie them to their feet. How did you educate yourself in Depression-era America?

SG: I wasn’t quite sure at first that this was the era I’d set the story in. A circus photo set me off on the path of the novel, but then I got on a sidetrack about hobos and I realized that something like 80 percent of them were under twenty-one. You think about hobos and you imagine middle-aged, dirty men by the side of the track, but no, they were kids.

DW: So much happens on the train or just off the train. It’s the book’s main setting.

SG: The whole of a circus worker’s social life happened on a moving train. When they were off, they were setting up or they were performing or they were tearing down, so everything happened while they were moving. Once they collected your quarter, they did their act and then they got out. You were leaving by the front end of the tent, and they were hauling the benches out by the back end—they’re done, they’re finished, they want to get on the train.

SG: For Water for Elephants, which was the first historical thing I’ve written, I did all the research ahead of time. I needed to feel that I knew the subject matter in and out. I hate outlining. I hate outlines, hate them, hate them. I usually know what the crisis of the book is going to be, though I don’t know how I’m going to get there. I try to make it bad enough that I don’t know how I’m going to get out of it. And when I get there, I have to get out of it. I just get myself geared up, and I write every day and see what happens.

DW: Has your technical-writing background helped, or has it been a hindrance?

SG: It was great training. For one thing, it taught me to sit down and write for eight hours a day. For another, it taught me not to take personally editorial comments. The first instructional project I gave to an editor ten years ago came back covered in red. I was practically in tears. It has to be a thousand times worse if it’s a piece of fiction, but I don’t take it personally anymore.

DW: Did you get up close and personal to elephants in your research?

SG: At the Kansas City Zoo, I observed the elephants with their ex-handler for a couple of days, taking notes on body language and behavior. I got into the habit of walking up to elephant handlers at the circus and saying, “Hi. I’m writing a book. May I meet your elephant?” I got lucky twice. The first time was right after I’d been out with this elephant handler at the Kansas City Zoo who had been gored by an elephant. He took a tusk through the thigh, one through the rib cage, which just missed everything vital, and another through his upper arm. So I still had that in mind. I was standing beside this huge thing with his amber eye staring down at me.

The guy said, “Go ahead. You can touch her.” I was shaking, but I touched her. I said, “Okay, I’m done now.” Several months later, I met the second one. It was one of these little circuses that throws a tent up and says, “Free tickets!” And then it’s twenty-dollar popcorn. I snuck out of the big top because it was small and pretty cheesy, but during the show I asked to meet the elephant; the handler gave me a bucket of peanuts and stuck me in an enclosure with this thing. He shut the gate. I was alone with this African elephant. I was looking at her, and she was looking at me like, This is not part of the usual repertoire. So I fed her the peanuts. By the end of it, she was such a love bug. I was hugging her and kissing her, posing for photos. She gave me a kiss, a big, sock puppet, mushy elephant kiss with the end of her trunk. It was really memorable.

Sara Gruen’s website

Elizabeth Judd’s review at the International Herald-Tribune

In a pool of sand and silt a starfish had thrust its arms up stiffly and was holding its body away from the stifling mud.

In a pool of sand and silt a starfish had thrust its arms up stiffly and was holding its body away from the stifling mud.

Earlier, we wrote about

Earlier, we wrote about  Wroblewski comments on the Hachiko link:

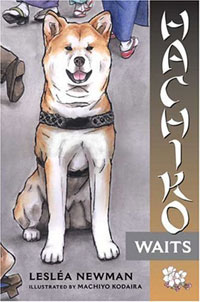

Wroblewski comments on the Hachiko link: Hachikō Waits is a children’s book, written by Lesléa Newman and illustrated by Machiyo Kodaira. It uses the true story of Hachikō the Akita dog from Japan and adds Yasuo, a young boy, to the story. It won the

Hachikō Waits is a children’s book, written by Lesléa Newman and illustrated by Machiyo Kodaira. It uses the true story of Hachikō the Akita dog from Japan and adds Yasuo, a young boy, to the story. It won the  Hachikō was given away after his master’s death, but he routinely escaped, showing up again and again at his old home. After time, Hachikō apparently realized that Professor Ueno no longer lived at the house. So he went to look for his master at the train station where he had accompanied him so many times before. Each day, Hachikō waited for Professor Ueno to return. And each day he didn’t see his friend among the commuters at the station.

Hachikō was given away after his master’s death, but he routinely escaped, showing up again and again at his old home. After time, Hachikō apparently realized that Professor Ueno no longer lived at the house. So he went to look for his master at the train station where he had accompanied him so many times before. Each day, Hachikō waited for Professor Ueno to return. And each day he didn’t see his friend among the commuters at the station. That same year, another of Ueno’s former students (who had become something of an expert on the Akita breed) saw the dog at the station and followed him to the Kobayashi home where he learned the history of Hachikō’s life. Shortly after this meeting, the former student published a documented census of Akitas in Japan. His research found only 30 purebred Akitas remaining, including Hachikō from Shibuya Station.

That same year, another of Ueno’s former students (who had become something of an expert on the Akita breed) saw the dog at the station and followed him to the Kobayashi home where he learned the history of Hachikō’s life. Shortly after this meeting, the former student published a documented census of Akitas in Japan. His research found only 30 purebred Akitas remaining, including Hachikō from Shibuya Station. Moon and Star: A Christmas Story is a beautiful and heart-warming picture book for the season by writer and illustrator, Robin Muller.

Moon and Star: A Christmas Story is a beautiful and heart-warming picture book for the season by writer and illustrator, Robin Muller. On Christmas Eve, a rich woman buys Star, and Moon is heartbroken.

On Christmas Eve, a rich woman buys Star, and Moon is heartbroken.

Many audience members weep openly. When the play reaches its moving climax, it sends them to their feet in rapturous applause.

Many audience members weep openly. When the play reaches its moving climax, it sends them to their feet in rapturous applause.

Aldo Leopold (1887 – 1948) was an American ecologist, forester and environmentalist. He was influential in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness preservation. He has been called an American prophet, the father of wildlife management, and one of most strongest advocates for conservation.

Aldo Leopold (1887 – 1948) was an American ecologist, forester and environmentalist. He was influential in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness preservation. He has been called an American prophet, the father of wildlife management, and one of most strongest advocates for conservation. Drawing from the entire corpus of Leopold’s works, including published and unpublished writing, correspondence, field notes, and journals, Flader places Leopold in his historical context. In addition, a biographical sketch draws on personal interviews with family, friends, and colleagues to illuminate his many roles as scientist, philosopher, citizen, policy maker, and teacher. Flader’s insight and profound appreciation of the issues make Thinking Like a Mountain a standard source for readers interested in Leopold scholarship and the development of ecology and conservation in the twentieth century.

Drawing from the entire corpus of Leopold’s works, including published and unpublished writing, correspondence, field notes, and journals, Flader places Leopold in his historical context. In addition, a biographical sketch draws on personal interviews with family, friends, and colleagues to illuminate his many roles as scientist, philosopher, citizen, policy maker, and teacher. Flader’s insight and profound appreciation of the issues make Thinking Like a Mountain a standard source for readers interested in Leopold scholarship and the development of ecology and conservation in the twentieth century.

Don Domanski was born and raised on Cape Breton Island and now lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His latest work, All Our Wonder Unavenged (Brick Books) recently won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry.

Don Domanski was born and raised on Cape Breton Island and now lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His latest work, All Our Wonder Unavenged (Brick Books) recently won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry. Riley’s family celebrates Jasper’s last day. In the morning, their beloved Golden Retriever gets his very own serving of his favourite breakfast – scrambled eggs with cheese, and bacon. Riley remembers to bring the camera as he and his family take Jasper out for a ride in the van.

Riley’s family celebrates Jasper’s last day. In the morning, their beloved Golden Retriever gets his very own serving of his favourite breakfast – scrambled eggs with cheese, and bacon. Riley remembers to bring the camera as he and his family take Jasper out for a ride in the van.